Rabindranath Tagore Biography – The Great Indian Poet and Nobel Prize Winner

Rabindranath Tagore FRAS was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He reshaped Bengali literature and music as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

| Quick Info→ | |

|---|---|

| Real Name: | Rabindranath Tagore |

| Profession: | Indian poet |

| Birthplace: | Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Kolkata, West Bengal, India) |

| Spouse: | Mrinalini Devi |

| Age: | 80 years |

Rabindranath Tagore FRAS (Bengali: রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর, /rəˈbɪndrənɑːt tæˈɡɔːr/ (![]() listen); 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He reshaped Bengali literature and music as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful” poetry of Gitanjali, he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Tagore’s poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; however, his “elegant prose and magical poetry” remain largely unknown outside Bengal. He was a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society. Referred to as “the Bard of Bengal”, Tagore was known by sobriquets: Gurudev, Kobiguru, Biswakobi.

listen); 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He reshaped Bengali literature and music as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful” poetry of Gitanjali, he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Tagore’s poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; however, his “elegant prose and magical poetry” remain largely unknown outside Bengal. He was a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society. Referred to as “the Bard of Bengal”, Tagore was known by sobriquets: Gurudev, Kobiguru, Biswakobi.

A Bengali Brahmin from Calcutta with ancestral gentry roots in the Burdwan district and Jessore, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old. At the age of sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhānusiṃha (“Sun Lion”), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics. By 1877 he graduated to his first short stories and dramas, published under his real name. As a humanist, universalist, internationalist, and ardent anti-nationalist, he denounced the British Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy also endures in his founding of Visva-Bharati University.

|

Rabindranath Tagore Biography

FRAS

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | Rabindranath Thakur 7 May 1861, 25th of Baishakh, 1268 (Bengali calendar) Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Kolkata, West Bengal, India) |

| Died | 7 August 1941 (aged 80) Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Kolkata, West Bengal, India) |

| Resting place | Ashes scattered in the Ganges |

| Pen name | Bhanusingha |

| Occupation |

|

| Language |

|

| Period | Bengali Renaissance |

| Literary movement | Contextual Modernism |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1913 |

| Spouse |

Mrinalini Devi (m. 1883; wid. 1902)

|

| Children | 5, including Rathindranath Tagore |

| Relatives | Tagore family |

| Signature | |

Table of Contents

Family history (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

The name Tagore is the anglicized transliteration of Thakur. The original surname of the Tagores was Kushari. They were Rarhi Brahmins and originally belonged to a village named Kush in the district named Burdwan in West Bengal. The biographer of Rabindranath Tagore, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyaya wrote in the first volume of his book Rabindrajibani O Rabindra Sahitya Prabeshak that

The Kusharis were the descendants of Deen Kushari, the son of Bhatta Narayana; Deen was granted a village named Kush (in Burdwan zilla) by Maharaja Kshitisura, he became its chief and came to be known as Kushari.

Life and events (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Early life: 1861–1878

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed “Rabi”) was born on 7 May 1861 in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta, the son of Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875).

Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father traveled widely. The Tagore family was at the forefront of the Bengal renaissance. They hosted the publication of literary magazines; theatre and recitals of Bengali and Western classical music featured there regularly. Tagore’s father invited several professional Dhrupad musicians to stay in the house and teach Indian classical music to the children. Tagore’s oldest brother Dwijendranath was a philosopher and poet. Another brother, Satyendranath, was the first Indian appointed to the elite and formerly all-European Indian Civil Service. Yet another brother, Jyotirindranath, was a musician, composer, and playwright. His sister Swarnakumari became a novelist. Jyotirindranath’s wife Kadambari Devi, slightly older than Tagore, was a dear friend and powerful influence. Her abrupt suicide in 1884, soon after he married, left him profoundly distraught for years.

Tagore largely avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or nearby Bolpur and Panihati, which the family visited. His brother Hemendranath tutored and physically conditioned him by having him swim the Ganges or trek through hills, gymnastics, and practicing judo and wrestling. He learned drawing, anatomy, geography and history, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit, and English—his least favorite subject. Tagore loathed formal education—his scholarly travails at the local Presidency College spanned a single day. Years later he held that proper teaching does not explain things; proper teaching stokes curiosity.

Shelaidaha: 1878–1901

Because Debendranath wanted his son to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878. He stayed for several months at a house that the Tagore family owned near Brighton and Hove, in Medina Villas; in 1877 his nephew and niece—Suren and Indira Devi, the children of Tagore’s brother Satyendranath—were sent together with their mother, Tagore’s sister-in-law, to live with him. He briefly read law at University College London, but again left school, opting instead for independent study of Shakespeare’s plays Coriolanus, Antony and Cleopatra, and the Religio Medici of Thomas Browne. Lively English, Irish, and Scottish folk tunes impressed Tagore, whose own tradition of Nidhubabu-authored kirtans and tappas and Brahmo hymnody was subdued. In 1880 he returned to Bengal degreeless, resolving to reconcile European novelty with Brahmo traditions, taking the best from each. After returning to Bengal, Tagore regularly published poems, stories, and novels. These had a profound impact on Bengal itself but received little national attention. In 1883 he married 10-year-old Mrinalini Devi, born Bhabatarini, 1873–1902 (this was a common practice at the time). They had five children, two of whom died in childhood.

Santiniketan: 1901–1932

In 1901 Tagore moved to Santiniketan to found an ashram with a marble-floored prayer hall—The Mandir—an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, and a library. There his wife and two of his children died. His father died in 1905. He received monthly payments as part of his inheritance and income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family’s jewelry, his seaside bungalow in Puri, and a derisory 2,000 rupees in book royalties. He gained Bengali and foreign readers alike; he published Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) and translated poems into free verse.

In 1912, Tagore translated his 1910 work Gitanjali into English. While on a trip to London, he shared these poems with admirers including William Butler Yeats and Ezra Pound. London’s India Society published the work in a limited edition, and the American magazine Poetry published a selection from Gitanjali. In November 1913, Tagore learned he had won that year’s Nobel Prize in Literature: the Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic—and for Westerners—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material focused on the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings. He was awarded a knighthood by King George V in the 1915 Birthday Honours, but Tagore renounced it after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Renouncing the knighthood, Tagore wrote in a letter addressed to Lord Chelmsford, the then British Viceroy of India, “The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilized governments…The time has come when badges of honor make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of my countrymen.”

Twilight years: 1932–1941

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore’s life as being one of a “peripatetic litterateur”. It affirmed his opinion that human divisions were shallow. During a May 1932 visit to a Bedouin encampment in the Iraqi desert, the tribal chief told him that “Our Prophet has said that a true Muslim is he by whose words and deeds not the least of his brother-men may ever come to any harm …” Tagore confided in his diary: “I was startled into recognizing in his words the voice of essential humanity.” To the end Tagore scrutinized orthodoxy—and in 1934, he struck. That year, an earthquake hit Bihar and killed thousands. Gandhi hailed it as seismic karma, as divine retribution avenging the oppression of Dalits. Tagore rebuked him for his seemingly ignominious implications. He mourned the perennial poverty of Calcutta and the socioeconomic decline of Bengal and detailed these newly plebeian aesthetics in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision foreshadowed Satyajit Ray’s film Apur Sansar. Fifteen new volumes appeared, among them, prose-poem works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). Experimentation continued in his prose songs and dance dramas— Chitra (1914), Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938)— and in his novels— Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934).

Travels

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents. In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others. Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali; Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. In November 1912 Tagore began touring the United States and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews’s clergymen friends. From May 1916 until April 1917, he lectured in Japan and the United States. He denounced nationalism. His essay “Nationalism in India” was scorned and praised; it was admired by Romain Rolland and other pacifists.

Shortly after returning home, the 63-year-old Tagore accepted an invitation from the Peruvian government. He traveled to Mexico. Each government pledged US$100,000 to his school to commemorate the visits. A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires, an ill Tagore shifted to the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo. He left for home in January 1925. In May 1926 Tagore reached Naples; the next day he met Mussolini in Rome. Their warm rapport ended when Tagore pronounced upon Il Duce‘s fascist finesse. He had earlier enthused: “[w]ithout any doubt he is a great personality. There is such a massive vigour in that head that it reminds one of Michael Angelo’s chisel.” A “fire-bath” of fascism was to have educed “the immortal soul of Italy … clothed in quenchless light”.

Works

Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore’s prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from the lives of common people. Tagore’s non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Europe Jatrir Patro (Letters from Europe) and Manusher Dhormo (The Religion of Man). His brief chat with Einstein, “Note on the Nature of Reality”, is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore’s 150th birthday, an anthology (titled Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali) of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes. In 2011, Harvard University Press collaborated with Visva-Bharati University to publish The Essential Tagore, the largest anthology of Tagore’s works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore’s birth.

Drama (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Tagore’s experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — Valmiki Pratibha which was shown at the Tagore’s mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate “the play of feeling and not of action”. In 1890 he wrote Visarjan (an adaptation of his novella Rajarshi), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore’s dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play Dak Ghar (The Post Office; 1912), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately “fall[ing] asleep”, hinting at his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore’s words, “spiritual freedom” from “the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds”. Another is Tagore’s Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modeled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha’s disciple, asks a tribal girl for water. Raktakarabi (“Red” or “Blood Oleanders”) is an allegorical struggle against a kleptocrat king who rules over the residents of Yaksha puri.

Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya.

Short stories

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with “Bhikharini” (“The Beggar Woman”). With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre. The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore’s “Sadhana” period (named for one of Tagore’s magazines). This period was among Tagore’s most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories. Such stories usually showcase Tagore’s reflections on his surroundings, modern and fashionable ideas, and interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the “Sadhana” period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore’s life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family’s vast landholdings. There, he beheld the lives of India’s poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point. In particular, such stories as “Kabuliwala” (“The Fruitseller from Kabul”, published in 1892), “Kshudita Pashan” (“The Hungry Stones”) (August 1895), and “Atithi” (“The Runaway”, 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden. Many of the other Galpaguchchha stories were written in Tagore’s Sabuj Patra period from 1914 to 1917, also named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to.

Novels (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them Chaturanga, Shesher Kobita, Char Odhay, and Noukadubi. Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)—through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil—excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement; a frank expression of Tagore’s conflicted sentiments, it emerged from a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil’s—likely mortal—wounding.

Gora raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jāti), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle. In it, an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny is raised by Hindus as the titular gora—”whitey”. Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a “true dialectic” advancing “arguments for and against strict traditionalism”, it tackles the colonial conundrum by “portray[ing] the value of all positions within a particular frame […] not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy but the extremest reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share.” Among these Tagore highlights “identity […] conceived of as dharma.”

Poetry (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Internationally, Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore’s best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and the second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after Theodore Roosevelt.

Besides Gitanjali, other notable works include Manasi, Sonar Tori (“Golden Boat”), Balaka (“Wild Geese” — the title being a metaphor for migrating souls).

Tagore’s poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen. Tagore’s most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon. These, rediscovered and repopularised by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasize inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhadralok religious and social orthodoxy. During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bāuls’ “man within the heart” and Tagore’s “life force of his deep recesses”, or meditating upon the Jeevan devata—the demiurge or the “living God within”. This figure is connected with divinity through an appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which were repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years.

Songs (Rabindra Sangeet)

Tagore was a prolific composer with around 2,230 songs to his credit. His songs are known as rabindrasangit (“Tagore Song”), which merge fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricised. Influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions. They emulated the tonal color of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga’s melody and rhythm faithfully; others newly blended elements of different ragas. Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with “fresh value” from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk, and other regional flavors “external” to Tagore’s own ancestral culture.

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written – ironically – to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: cutting off the Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a cunning plan to stop the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised form of Bengali, and is the first of five stanzas of the Brahmo hymn Bharot Bhagyo Bidhata that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem.

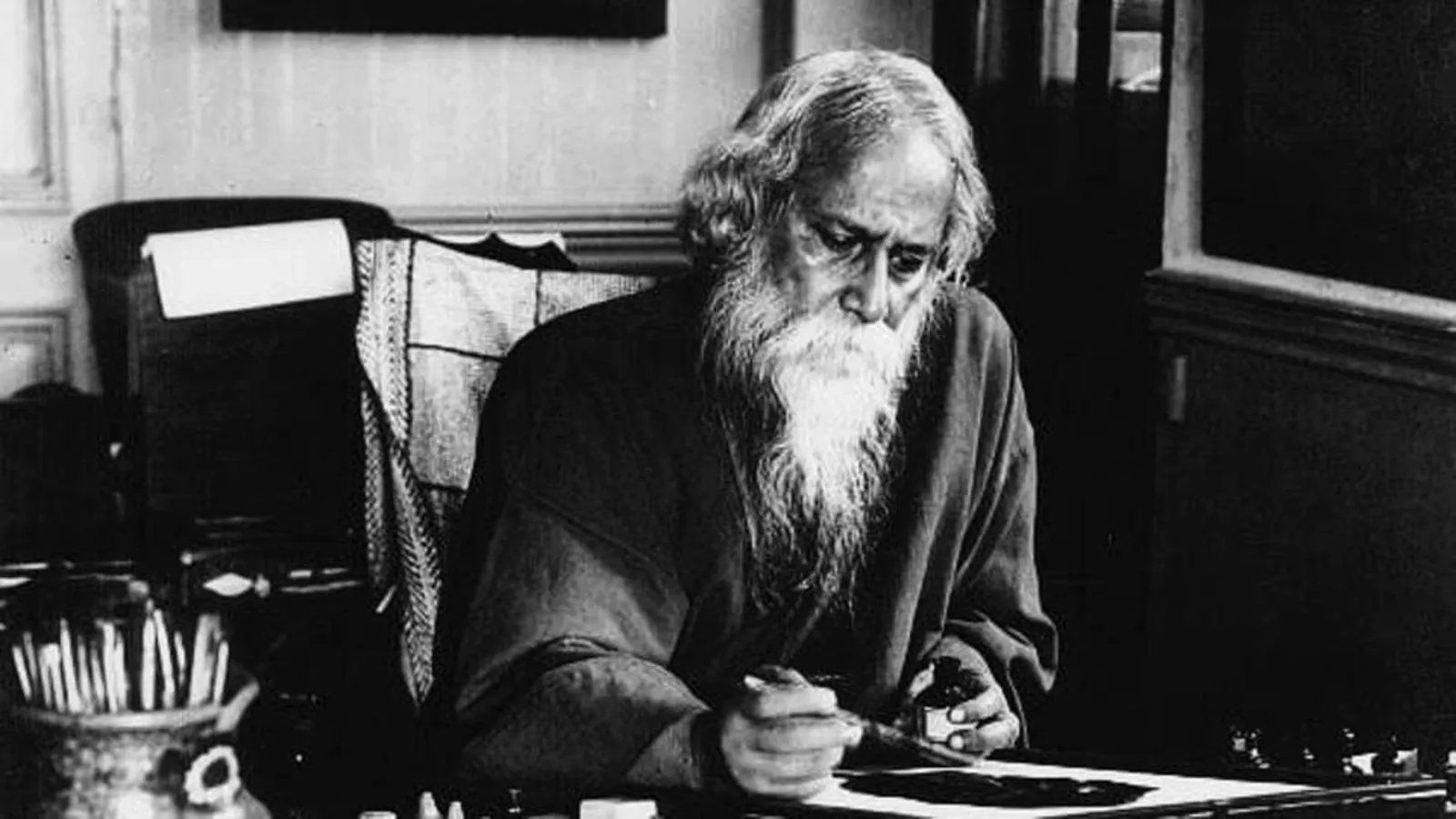

Artworks (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France—were held throughout Europe. He was likely red-green color blind, resulting in works that exhibited strange color schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by numerous styles, including scrimshaw by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein. His artist’s eye for handwriting was revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore’s lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.

Politics (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists, and these views were first revealed in Manast, which was mostly composed in his twenties. Evidence produced during the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial and later accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and former Premier Ōkuma Shigenobu. Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement; he rebuked it in The Cult of the Charkha, an acrid 1925 essay. According to Amartya Sen, Tagore rebelled against strongly nationalist forms of the independence movement, and he wanted to assert India’s right to be independent without denying the importance of what India could learn from abroad. He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of the British administration as a “political symptom of our social disease”. He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, “there can be no question of blind revolution”; preferable to it was a “steady and purposeful education”.

Repudiation of knighthood

Tagore renounced his knighthood in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. In the repudiation letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.

Santiniketan and Visva-Bharati (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling: in “The Parrot’s Training”, a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death. Tagore, visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, conceived a new type of university: he sought to “make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world [and] a world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography.” The school, which he named Visva-Bharati, had its foundation stone laid on 24 December 1918 and was inaugurated precisely three years later. Tagore employed a brahmacharya system: gurus gave pupils personal guidance—emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. Teaching was often done under trees. He staffed the school, he contributed his Nobel Prize monies, and his duties as steward-mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy: in mornings he taught classes; in afternoons and evenings he wrote the students’ textbooks. He fundraised widely for the school in Europe and the United States between 1919 and 1921.

Theft of Nobel Prize

On 25 March 2004, Tagore’s Nobel Prize was stolen from the safety vault of the Visva-Bharati University, along with several other of his belongings. On 7 December 2004, the Swedish Academy decided to present two replicas of Tagore’s Nobel Prize, one made of gold and the other made of bronze, to the Visva-Bharati University. It inspired the fictional film Nobel Chor. In 2016, a Baul singer named Pradip Bauri accused of sheltering the thieves was arrested and the prize was returned.

Impact and legacy (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: Kabipranam, his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois (USA); Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages from Kolkata to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries. Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a “towering figure”, a “deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker”. Tagore’s Bengali originals—the 1939 Rabīndra Rachanāvalī—are canonized as one of his nation’s greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: “the greatest poet India has produced”.

Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded Dartington Hall School, a progressive coeducational institution; in Japan, he influenced such figures as Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata. In colonial Vietnam Tagore was a guide for the restless spirit of the radical writer and publicist Nguyen An Ninh Tagore’s works were widely translated into English, Dutch, German, Spanish, and other European languages by Czech Indologist Vincenc Lesný, French Nobel laureate André Gide, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, former Turkish Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, and others. In the United States, Tagore’s lecturing circuits, particularly those of 1916–1917, were widely attended and wildly acclaimed. Some controversies involving Tagore, possibly fictive, trashed his popularity and sales in Japan and North America after the late 1920s, concluding with his “near total eclipse” outside Bengal. Yet a latent reverence for Tagore was discovered by an astonished Salman Rushdie during a trip to Nicaragua.

Museums (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

- Rabindra Bharati Museum, at Jorasanko Thakur Bari, Kolkata, India

- Tagore Memorial Museum, at Shilaidaha Kuthibadi, Shilaidaha, Bangladesh

- Rabindra Memorial Museum at Shahzadpur Kachharibari, Shahzadpur, Bangladesh

- Rabindra Bhavan Museum, in Santiniketan, India

- Rabindra Museum, in Mungpoo, near Kalimpong, India

- Patisar Rabindra Kacharibari, Patisar, Atrai, Naogaon, Bangladesh

- Pithavoge Rabindra Memorial Complex, Pithavoge, Rupsha, Khulna, Bangladesh

- Rabindra Complex, Dakkhindihi village, Phultala Upazila, Khulna, Bangladesh

Jorasanko Thakur Bari (Bengali: House of the Thakurs; anglicized to Tagore) in Jorasanko, north of Kolkata, is the ancestral home of the Tagore family. It is currently located on the Rabindra Bharati University campus at 6/4 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane Jorasanko, Kolkata 700007. It is the house in which Tagore was born. It is also the place where he spent most of his childhood and where he died on 7 August 1941.

List of works (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

The SNLTR hosts the 1415 BE edition of Tagore’s complete Bengali works. Tagore Web also hosts an edition of Tagore’s works, including annotated songs. Translations are found on Project Gutenberg and Wikisource. More sources are below.

Original

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| ভানুসিংহ ঠাকুরের পদাবলী | Bhānusiṃha Ṭhākurer Paḍāvalī | Songs of Bhānusiṃha Ṭhākur | 1884 |

| মানসী | Manasi | The Ideal One | 1890 |

| সোনার তরী | Sonar Tari | The Golden Boat | 1894 |

| গীতাঞ্জলি | Gitanjali | Song Offerings | 1910 |

| গীতিমাল্য | Gitimalya | Wreath of Songs | 1914 |

| বলাকা | Balaka | The Flight of Cranes | 1916 |

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| বাল্মিকী প্রতিভা | Valmiki-Pratibha | The Genius of Valmiki | 1881 |

| কালমৃগয়া | Kal-Mrigaya | The Fatal Hunt | 1882 |

| মায়ার খেলা | Mayar Khela | The Play of Illusions | 1888 |

| বিসর্জন | Visarjan | The Sacrifice | 1890 |

| চিত্রাঙ্গদা | Chitrangada | Chitrangada | 1892 |

| রাজা | Raja | The King of the Dark Chamber | 1910 |

| ডাকঘর | Dak Ghar | The Post Office | 1912 |

| অচলায়তন | Achalayatan | The Immovable | 1912 |

| মুক্তধারা | Muktadhara | The Waterfall | 1922 |

| রক্তকরবী | Raktakarabi | Red Oleanders | 1926 |

| চণ্ডালিকা | Chandalika | The Untouchable Girl | 1933 |

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| নষ্টনীড় | Nastanirh | The Broken Nest | 1901 |

| গোরা | Gora | Fair-Faced | 1910 |

| ঘরে বাইরে | Ghare Baire | The Home and the World | 1916 |

| যোগাযোগ | Yogayog | Crosscurrents | 1929 |

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| জীবনস্মৃতি | Jivansmriti | My Reminiscences | 1912 |

| ছেলেবেলা | Chhelebela | My Boyhood Days | 1940 |

| Title | Year |

|---|---|

| Thought Relics | 1921 |

Translated

| Year | Work |

|---|---|

| 1914 | Chitra |

| 1922 | Creative Unity |

| 1913 | The Crescent Moon |

| 1917 | The Cycle of Spring |

| 1928 | Fireflies |

| 1916 | Fruit-Gathering |

| 1916 | The Fugitive |

| 1913 | The Gardener |

| 1912 | Gitanjali: Song Offerings |

| 1920 | Glimpses of Bengal |

| 1921 | The Home and the World |

| 1916 | The Hungry Stones |

| 1991 | I Won’t Let you Go: Selected Poems |

| 1914 | The King of the Dark Chamber |

| 2012 | Letters from an Expatriate in Europe |

| 2003 | The Lover of God |

| 1918 | Mashi |

| 1943 | My Boyhood Days |

| 1917 | My Reminiscences |

| 1917 | Nationalism |

| 1914 | The Post Office |

| 1913 | Sadhana: The Realisation of Life |

| 1997 | Selected Letters |

| 1994 | Selected Poems |

| 1991 | Selected Short Stories |

| 1915 | Songs of Kabir |

| 1916 | The Spirit of Japan |

| 1918 | Stories from Tagore |

| 1916 | Stray Birds |

| 1913 | Vocation |

| 1921 | The Wreck |

Adaptations of novels and short stories in cinema (Rabindranath Tagore Biography)

Bengali

- Natir Puja – 1932 – The only film directed by Rabindranath Tagore

- Gora — 1938 Gora (novel) — Naresh Mitra

- Noukadubi– Nitin Bose

- Bou Thakuranir Haat – 1953 (Bou Thakuranir Haat) – Naresh Mitra

- Kabuliwala – 1957 (Kabuliwala) – Tapan Sinha

- Kshudhita Pashan – 1960 (Kshudhita Pashan) – Tapan Sinha

- Teen Kanya – 1961 (Teen Kanya) – Satyajit Ray

- Charulata – 1964 (Nastanirh) – Satyajit Ray

- Megh o Roudra – 1969 (Megh o Roudra) – Arundhati Devi

- Ghare Baire – 1985 (Ghare Baire) – Satyajit Ray

- Chokher Bali – 2003 (Chokher Bali) – Rituparno Ghosh

- Shasti – 2004 (Shasti) – Chashi Nazrul Islam

- Shuva – 2006 (Shuvashini) – Chashi Nazrul Islam

- Chaturanga – 2008 (Chaturanga) – Suman Mukhopadhyay

- Noukadubi – 2011 (Noukadubi) – Rituparno Ghosh

- Elar Char Adhyay – 2012 (Char Adhyay) – Bappaditya Bandyopadhyay

Hindi

- Sacrifice – 1927 (Balidan) – Nanand Bhojai and Naval Gandhi

- Milan – 1946 (Nauka Dubi) – Nitin Bose

- Dak Ghar – 1965 (Dak Ghar) – Zul Vellani

- Kabuliwala – 1961 (Kabuliwala) – Bimal Roy

- Uphaar – 1971 (Samapti) – Sudhendu Roy

- Lekin… – 1991 (Kshudhit Pashaan) – Gulzar

- Char Adhyay – 1997 (Char Adhyay) – Kumar Shahani

- Kashmakash – 2011 (Nauka Dubi) – Rituparno Ghosh

- Stories by Rabindranath Tagore (Anthology TV Series) – 2015 – Anurag Basu

- Bioscopewala – 2017 (Kabuliwala) – Deb Medhekar

- Bhikharin

In popular culture

- Rabindranath Tagore is a 1961 Indian documentary film written and directed by Satyajit Ray, released during the birth centenary of Tagore. It was produced by the Government of India’s Films Division.

- Serbian composer Darinka Simic-Mitrovic used Tagore’s text for her song cycle Gradinar in 1962.

- In Sukanta Roy’s Bengali film Chhelebela (2002) Jisshu Sengupta portrayed Tagore.

- In Bandana Mukhopadhyay’s Bengali film Chirosakha He (2007) Sayandip Bhattacharya played Tagore.

- In Rituparno Ghosh’s Bengali documentary film Jeevan Smriti (2011) Samadarshi Dutta played Tagore.

- In Suman Ghosh’s Bengali film Kadambari (2015) Parambrata Chatterjee portrayed Tagore.