Haryana CM Nayab Singh Saini | Younger legs for the race

Farm-fresh, caste-positive and no baggage—that’s what Khattar protege Nayab Singh Saini brings to the table as the BJP attempts a political makeover just before a brace of crucial polls in Haryana

The unexpected is to be expected: that’s by now a motto in the BJP’s tactical playbook. But it always leaves a vast pool of possibilities. Where—rather, against whose name—would the roulette’s needle stop? The tall, lanky, bearded figure of Nayab Singh Saini is where it decided to stop on March 12. Soft of manner and speech, and perhaps even of ambition, the 54-year-old MP from Kurukshetra may have been as surprised as Manohar Lal Khattar was back in 2014 when picked as the chief minister of Haryana. The latter had an equally surprising exit clause sprung on him, six months short of a decade in office. Just the previous day, as he walked down the spanking-new Dwarka Expressway with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the 69-year-old Khattar had seemed supremely secure in saddle and stirrup. Saini, an OBC, is counted among those loyal to him, but wasn’t ever really groomed to inherit the mantle, nor did he present himself as a frontline choice for a generational shift. That is, if at all Haryana was deemed ready for a replay of a maneuver the BJP has previously employed in Gujarat, Uttarakhand, and Karnataka, choosing to face voters under a new chief minister. Another jigsaw piece was dislodged alongside, perhaps to be refitted at a different time—the Dushyant Chautala-led Jannayak Janta Party (JJP), an ally that had helped it make up the numbers in 2014, was out.

What explains this great churn, this new ambush on the settled order of things? It’s not irrelevant that the BJP in Haryana has two encounters with the electorate on its to-do list: its 10 Lok Sabha seats will be a high-stakes game in the general election in the summer before the state votes for a new assembly in September. So this shift in power centers and rejigging of the legislator arithmetic, which also seeks to alter the caste equations, feeds both games at once.

In the 90-member assembly, the BJP has 41 MLAs. Plus, it has the support of five independents and two members of smaller parties. That suffices even without the JJP’s 10 MLAs, which lent stability to the Khattar regime over the years in return for three ministerial slots. Dushyant was deputy CM whereas his grand uncle Ranjit Chautala—Om Prakash Chautala’s younger brother—was ranked below him in the cabinet. This flock of 10 may not stay intact, if the absence of five MLAs from a JJP meeting on March 12 is any indication. But the prospect of a splinter group from a smaller ally joining up with the BJP—a recurrent motif across states—would be a minor detail. What’s of more interest is the role the JJP will play in the Lok Sabha polls, as a Jat-based outfit now seen to be done in by the BJP.

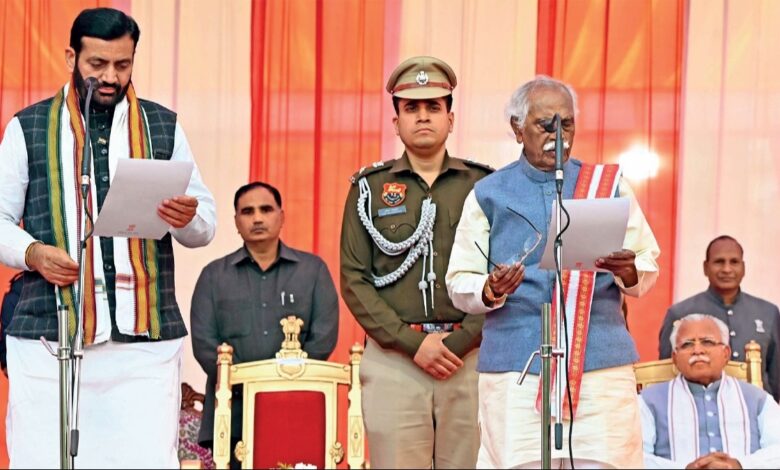

The JJP’s inner circles weren’t the only place hit by a spot of restiveness. Saini inherited the Khattar cabinet minus not only the three JJP representatives. A prominent BJP face was missing too—that of Anil Vij, Khattar’s friend-cum-foe, who refused to be part of the new cabinet. Vij, who represents Ambala in the assembly, is presently the BJP’s longest-serving legislator and thus has reason to feel aggrieved. Not only does he feel Saini is too junior to be his boss, Vij has had issues with him in the past. And so the party witnessed the rare spectacle of a sulking veteran staging an exit from a swearing-in ceremony—that too, symbolically, in a non-official car. Later in the day, Khattar told scribes that Vij was supposed to join the cabinet, but got upset and the party leadership is trying to assuage his hurt.

Saini is a long-time confidant of Khattar, starting as his political assistant in 1996. He got his first ticket to run for the assembly, from Naraingarh in Ambala district, on Khattar’s recommendation in 2010. He lost his deposit. In 2014, Khattar managed to coax the leadership into giving him a second chance, and the Modi wave that year took him to victory—and a junior minister’s place in Khattar’s first cabinet. And last October, in a demonstration of his clout, Khattar had persuaded the central command to replace a bete noire with Saini as state unit chief. The big challenge for the understudy, therefore, will be to break out of the shadows of the guru, and quickly. He has little time to do so. Once the dates are announced for the general election, any day now, the model code of conduct will limit his policy space for three months.

But for now, Saini may just need to be himself—and symbolically represent what he does. Khattar, an unmarried RSS pracharak from an urban Punjabi Khatri family, never exuded the vibes of the organically farmed Haryana politician. Unlike him, Saini belongs to a native, agrarian, non-Jat OBC community. There’s strong strategic continuity here: His job is to consolidate the rainbow of non-Jats created by Khattar—a vital collage of castes. In both the Lok Sabha and assembly polls of 2019, 70 percent of the non-Jats had voted BJP.

Vital also because the Jats—Haryana’s dominant agrarian community, numbering about 27 percent of the populace and key to a whole swathe of seats—have for years often inhabited a zone of sullen alienation, extending to anger, vis- -vis the BJP. The sense of distance from power began when Khattar was chosen in 2014—after a decade of the Congress’s Jat patriarch Bhupinder Singh Hooda as CM—despite overwhelming Jat support for Modi in 2014. Things never really reached an even keel thereafter. Instead, the past decade saw a series of aggravating events: the violent 2016 Jat quota agitation, the waves of farmer protests, the wrestlers’ protest in Delhi that saw organic khap support for female Jat sportspersons from Haryana on what was perceived, and propagated, as a matter of community honor. Despite his innovative crop pricing policies that benefited all and gave Haryana a robust 8.1 percent agricultural growth in FY24, the recent tinderbox situation with Punjab’s protesting farm unions could have deepened Jat alienation across the entire Green Revolution cluster of states.